Photo: Roberto Schmidt/AFP/Getty Images

Photo: Roberto Schmidt/AFP/Getty Images

If you are an aficionado of wonky policy debates, or perhaps if you are a civically active Californian, you may have heard there’s a debate going on in left-of-center circles over a so-called “Abundance Agenda.” That term was coined in 2022 by Derek Thompson, whose recent book with Ezra Klein, entitled Abundance, has helped raise interest (and some hackles) over its tenets. Put briefly, “abundance” advocates believe progressive politics needs to be refocused around producing public and private goods that broadly raise living standards, instead of insisting on narrow and legalistic group agendas that often frustrate the operations of government, particularly with respect to prosperity-enhancing public projects.

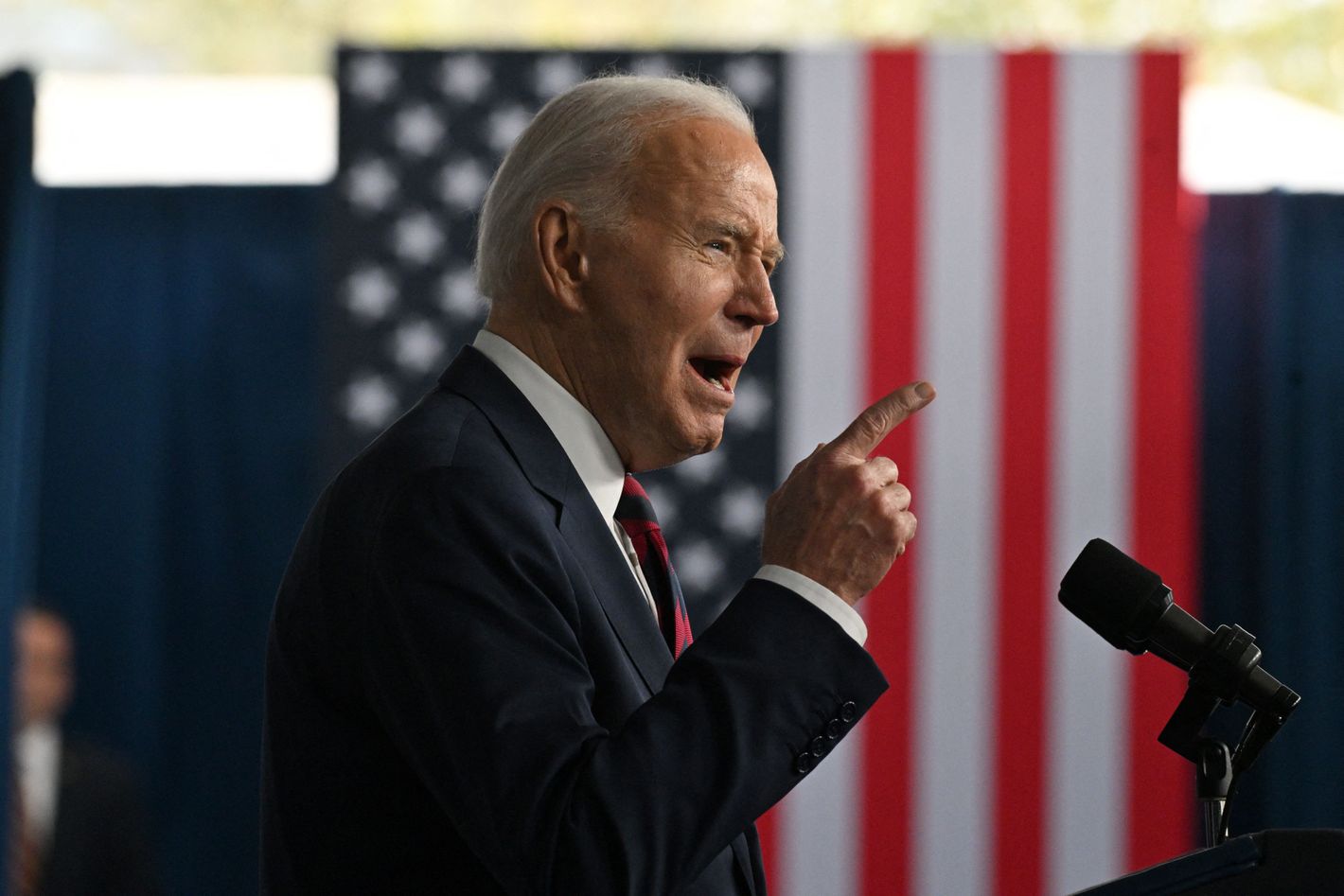

The leading edge of this debate has been the issue that is in danger of consuming California politics: the massive regulatory and legal obstacles to creating an adequate supply of affordable housing for sale or rent. But as my former colleague Jonathan Chait points out at The Atlantic, the recent experience of the Biden administration has really intensified concerns that progressives are sabotaging themselves by embracing interest-group-driven roadblocks to getting things done:

Biden had anticipated, after quickly signing his infrastructure bill and then two more big laws pumping hundreds of billions of dollars into manufacturing and energy, that he would spend the rest of his presidency cutting ribbons at gleaming new bridges and plants. But only a fraction of the funds Biden had authorized were spent before he began his reelection campaign, and of those, hardly any yielded concrete results.

More than two years after signing the infrastructure law, Biden was “expressing deep frustration that he can’t show off physical construction of many projects that his signature legislative accomplishments will fund,” CNN reported. The nationwide network of electric-vehicle-charging stations amounted to just 58 new stations by the time Biden left office. The average completion date for road projects, according to the nonprofit news site NOTUS, was mid-2027. The effort to bring broadband access to rural America, a centerpiece of Biden’s plan to show that he would work to help the entire country and not just the parts that had voted for him, had connected zero customers.

The fateful failure of Biden’s Build Back Better agenda contributed, of course, to the opportunity Donald Trump had to become president again and launch his own very different BBB. And as Chait observed, that realization led to a lot of reconsiderations of prior assumptions:

Policy wonks, mostly liberal ones, began to ask why public tasks that used to be doable no longer were. How could a government that once constructed miracles of engineering—the Hoover Dam, the Golden Gate Bridge—ahead of schedule and under budget now find itself incapable of executing routine functions? Why was Medicare available less than a year after the enabling legislation passed, when the Affordable Care Act’s individual-insurance exchange took nearly four years to come online (and had to survive a failed website)? And, more disturbing, why was everything slower, more expensive, and more dysfunctional in states and cities controlled by Democrats?

The obvious conclusion is that if “the government has tied itself in knots … enormous amounts of prosperity could be unleashed by simply untying them.” But “untying them” would offend the progressive interest and identity groups who had built up an edifice of safeguards against potentially abusive government power, and whose entire approach to politics involved defending each other’s regulatory and legal turf. So any effort to ride roughshod over these safeguards, even in the most unimpeachably progressive causes like battling homelessness, has drawn a lot of fire from the left and “the groups” (as various interest and identity advocates are often called).

The rivalry between “common purpose” liberals seeking to do good things quickly through government, and progressives affiliated with various “groups,” is a lot older than the arguments over “abundance.” Reading Chait’s description of a progressivism that “seeks to maintain solidarity among its component groups, expecting each to endorse the positions taken by the others” reminded me instantly of one of the best political speeches I ever heard, at the 1988 Democratic National Convention, by the Reverend Jesse Jackson, who said his piece before delivering his endorsement to party presidential nominee Michael Dukakis:

When I was a child growing up in Greenville, South Carolina, my grandmama could not afford a blanket, she didn’t complain and we did not freeze. Instead she took pieces of old cloth — patches, wool, silk, gabardine, crockersack — only patches, barely good enough to wipe off your shoes with. But they didn’t stay that way very long. With sturdy hands and a strong cord, she sewed them together into a quilt, a thing of beauty and power and culture. Now, Democrats, we must build such a quilt.

Farmers, you seek fair prices and you are right — but you cannot stand alone. Your patch is not big enough. Workers, you fight for fair wages, you are right — but your patch of labor is not big enough. Women, you seek comparable worth and pay equity, you are right — but your patch is not big enough.

And on through the litany of groups he went … students … Blacks and Hispanics … gays and lesbians, in every case their “patch” was not big enough alone. Jesse Jackson’s very clear vision was a Democratic Party that was a coalition of groups linking arms to protect their stuff, their solidarity more important than any particular thing that they might do together. And that’s the entrenched and emotionally compelling point of view the abundance advocates are trying to overcome. It’s a struggle that is also evident in separate discussions over the morality of policy positions that leave any vulnerable group less than fully empowered, such as restricting athletic opportunities for transgender women, a wildly popular but deeply offensive position from the point of view of progressive solidarity.

But here’s the thing: The current emergency created by Donald Trump’s 2024 election victory has given the abundance camp a powerful new argument. Had Joe Biden been able to implement his BBB and show results, might his performance on the economy have been viewed as superior to Trump’s? Possibly so. And if Democrats during his administration had made a visible effort to “reinvent government” to make it more efficient, would hostility to bureaucracy and alleged “runaway government spending” have been a potent issue for Trump? Possibly not.

What we do know is that Trump’s victory gave us an administration that is systematically working to destroy all the causes “the groups” hold dear. Instead of less rigid environmental regulations, we are seeing their total revocation in an ongoing frenzy to “drill baby drill.” Instead of less complicated and less litigation-based civil-rights protections for Black and Latino and LGBTQ+ people, we are watching as “civil rights” are redefined as exclusively for the protection of straight white Christians and Jews, while transgender folk are literally being defined out of existence. And instead of a “reinvented” government focused on achievement of defined public goals, the Trump administration is blowing up government and delegitimizing the very idea of public service. Everyone’s “patch is not big enough” today, but out-of-power Democrats can’t do much about it. “The groups” might develop an overriding stake in making things work and restoring the credibility of both the public sector and the progressive movement that built it over the decades. It could mean political as well as economic abundance for all.

From Intelligencer - Daily News, Politics, Business, and Tech via this RSS feed