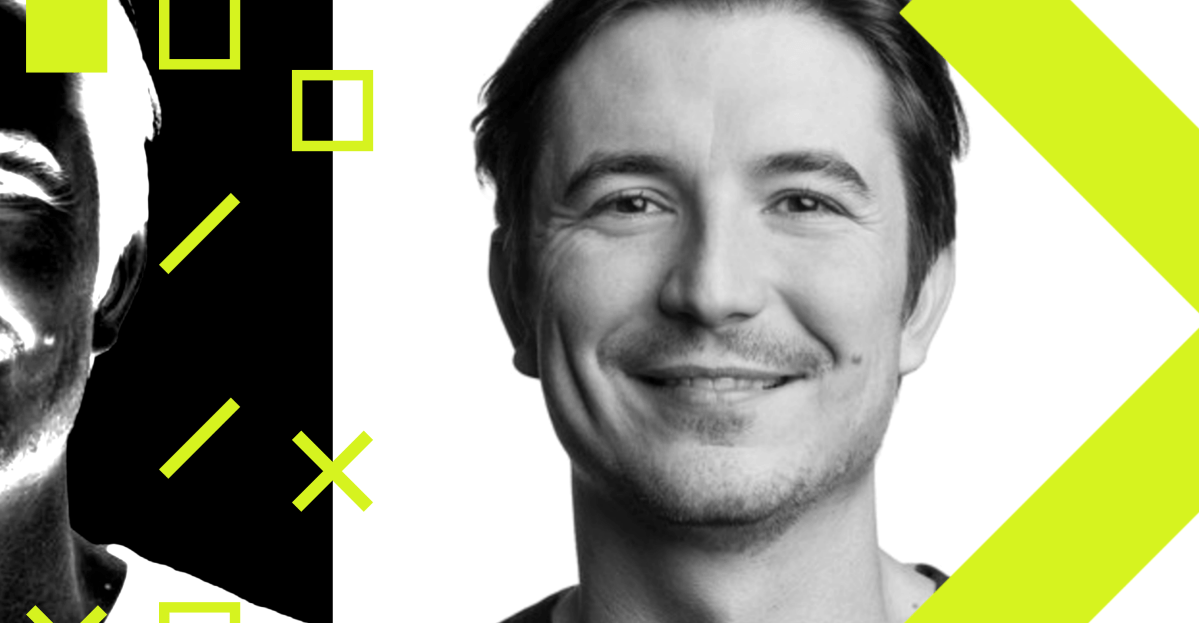

Today, I’m talking with Vlad Tenev, the cofounder and CEO of Robinhood, which is one of the most well-known consumer finance apps in the world. It started as a way to open up stock trading, but the company’s ambitions have grown over time — and they’re getting even bigger.

Just a day before Tenev and I talked, Robinhood announced it would soon be offering bank accounts and wealth management services, which would allow Robinhood to be involved with your money at every possible level.

So I was interested to sit down with Tenev and really hash out where Robinhood is going and why he’s so adamant that big ideas, like prediction markets based around everything from sports games to presidential elections, are going to play such a pivotal role in the future of finance. And I really wanted to talk about the responsibilities that come with that role.

Robinhood is on a lot of people’s phones — especially young men — and it’s a quick jump from doing a little bit of casual retail investing to potentially dumping all your money into a bunch of unpredictable, unstable markets. There’s a whole generation out there who might have bought a GameStop share as a joke during the COVID-19 pandemic and are now finding themselves consistently gambling in the crypto and prediction markets.

Listen to Decoder, a show hosted by The Verge’s Nilay Patel about big ideas — and other problems. Subscribe here!

Tenev and I really dug into some of the complexity around these ideas. For example, you’ll hear him say he thinks of prediction markets as “the news faster” and that there is a meaningful difference between a prediction market guessing if the Lakers will win their next game and just simply placing a bet on DraftKings or FanDuel for the same outcome. You’ll hear him say that prediction markets communicate unique information that reflects reality, rather than just a dressed-up version of gambling that mostly reflects how people feel.

You will also hear my deep skepticism of these ideas. I really pressed Tenev for answers on how he thinks about the risks involved, especially for regular retail investors, and whether the regulatory environment can keep up with that escalating amount of risk. It’s already causing problems: New Jersey and Nevada both ordered Robinhood to halt its prediction markets, and the company’s partner Kalshi launched lawsuits to push back.

You’ll hear Tenev say that he has no firm idea where any of this might go, but that he fundamentally believes people should get to do whatever they want with their money — and that he wants to position Robinhood as a central destination for all of those transactions.

That made me curious as to what Tenev sees as Robinhood’s ultimate destination. So I asked him outright: does he think Robinhood is just selling an updated version of the American dream, where you can make the right wager on a prediction, buy the right stock, or invest in the right meme coin to shortcut your way to financial freedom? I won’t spoil it, but I think you’ll find his answer pretty illuminating.

Like I said, you’re going to hear us disagree quite a bit throughout this episode, but I want to give Tenev credit: he was game to really sit in some of the ambiguity and controversy here and talk about it in ways that many in the crypto and finance worlds simply aren’t. I rather enjoyed this one, and I think you will, too.

Okay: Robinhood CEO Vlad Tenev. Here we go.

This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Vlad Tenev, you are the co-founder and CEO of Robinhood. Welcome to Decoder.

Thanks for having me, Nilay.

I have so much to talk to you about. I think I have 900 pages of questions for you. There’s a lot going on in financial services. You all just launched banking services. There’s a lot going on in crypto. I know you’re very interested in prediction markets. I have a million questions about that. So, if you’re game, I’d like to go through the Decoder questions about structure and decision making very fast at the top and then get to the rest. Are you okay with that?

Yeah. I’ll try to be brief.

Because usually I do all this windup, but I think people know what Robinhood is, and I think your ideas about where it’s going are really interesting. Let’s just start with Robinhood. You founded it, then you were the co-CEO for a minute with your co-founder, Baiju Bhatt. He went to become the chief creative officer, you became sole CEO, and then he left the company. Just talk about that set of choices. That’s a pattern we see in startups quite often. How did that all go down?

Yeah, I think we technically started as co-CEOs as well, although in the early stages things are always a little bit murky. And then what happened was in the early days of the company, roles don’t really matter because you’re 10 people and you’re all in one room and you’re doing what’s necessary to make the company win. We both didn’t really have any concrete finance, business, or even technical skills when we started the company.

We met in college. We were actually both physics majors at the time, and we were brought together by our love for physics. We wanted to seek to understand answers to the big questions like what happened before the Big Bang? Or my favorite one: how can we unify general relativity and quantum mechanics? That’s how we became good friends; we were banging our heads against the wall trying to do problem sets in physics and math in college.

Then we learned to build products and build businesses together. We were co-founders of a few companies before Robinhood. When we started Robinhood, we moved to San Francisco together. He became a designer. He literally bought a Wacom tablet and started designing. And I became an engineer. I still remember on the Caltrain ride from San Francisco down to Palo Alto, I would watch Paul Hagerty’s iOS development classes at 2X speed, and that’s how I learned to be an iOS engineer. So that was the division of labor; I was writing code, he was doing the designs. We built a team around that. Then we became managers, and then we became executives. I think at each point, we reassessed what we wanted to be spending our time on, how we could add the most value to the company.

When it became clear that we’re going to have executives and we’re going to be a public company, Baiju made the decision that he didn’t want to be the CEO of a public company — that didn’t feel like how he wanted to spend his time and his energy. So he took the chief creative officer role, and then I think a couple years ago came to the decision that he wanted to go back to the original passion when we met, which was doing things with a more overt math and physics component.

So he ended up starting another interesting company, Aetherflux, which aims to bring solar energy in a more efficient form down to Earth and targeting remote outposts and military locations where energy is sorely needed. So he went off to start that and is still a board member. As the company changes, I think we’re pretty good at reevaluating our roles and what we want to spend time doing, and it was just an organic evolution over time.

So much of our audience is people who build things and people who want to be founders, people who are at different stages of being a founder. I always say that no one ever talks about act two — going from managing people to being executives and managing managers. It seems like you have chosen you’re going to be the eye of the storm of the public company that’s changing how finance is done. Are you comfortable with that now? It’s been several years; you’ve been the CEO since 2020. Have you settled into that role?

Well, I don’t know. You can never be too comfortable. What I’ll tell you is the things that I enjoy, do tend to align pretty well with being a public company and the activities of a public company CEO, like communicating the vision and figuring out how we can distill it in a simple form. I love the idea that institutional power and things that normally would’ve been reserved for institutions are now, through technology, available to individuals. That’s very much part of the genesis of Robinhood. It was all about individual participation in equity markets.

As a public company, we allow individuals to participate in being shareholders of Robinhood in a much bigger way, and so we’ve been doing all sorts of things to change what being a public company looks like. We were among the first to actually engage retail [investors] in a substantive way in our IPO. I think, to my knowledge, we were one of the biggest, if not the biggest, in terms of retail IPO allocation at the time. We let Robinhood customers through the Robinhood app participate in our own IPO. Then we bought a company called Say Technologies that does shareholder communications. If you’ve listened to Tesla, Palantir, or Robinhood earnings calls, they take questions from retail via our Say Technologies platform.

Last quarter, we did a live video earnings call. That was actually very cool. I think the inspiration was a post-game interview at an NBA game. We were like, “That’s fun, what are the other settings where you have people that just went through something hard talking about it and it’s enjoyable to watch?” And I’m an NBA fan and I actually look forward to the post-game interviews. I want to see what they’re wearing. If it’s a big loss, then I want to hear LeBron James talking about what they could have done better. It’s also fun if they win.

I think news, entertainment, financial services, sports to some degree… these are all merging over time, and they’re part of our collective consciousness. I think retail investing is a big part of that. A big, enduring trend is power and capabilities that were formerly reserved for institutions going to the individual level. I think we can change a lot of things about what it’s like being a public company participating in earnings calls. Traditionally, they were viewed as a chore and nobody really liked doing it, and it was considered B.S. that you have to deal with that was a cost, but I think it as an opportunity. I think if executed appropriately, it’s another opportunity to get the message out. I enjoy doing that.

I’m still learning, and I don’t have it figured out yet, but I think we can discover new things and being a public company definitely provides us opportunities to do different things that we wouldn’t normally be able to do.

I want to come back to that theme of what it’s like to be the founder and CEO of a startup versus the public company CEO of what is now basically a bank. Those are different characters, and I’m going to come back to that theme a few times throughout this conversation. How is Robinhood structured now? You’ve had some changes, you’ve had some layoffs over the past few years. How have you organized the company now?

So we have a parent company, Robinhood Markets, Inc., and that’s publicly traded. We have a number of subsidiaries and we typically organize the subsidiaries by business line, but now we also have international businesses, so we’ve got some international subsidiaries. I’ve got general managers who are basically CEOs in their own right that report to me that manage the business. Steve Quirk, who’s our chief brokerage officer, is also the general manager of our brokerage business. He’s got a couple of broker dealers that he oversees, like Robinhood Financial and Robinhood Securities, which is our clearing firm. We’re essentially a vertically integrated brokerage business under Steve Quirk.

Then we’ve got Johann Kerbrat, who’s our general manager of crypto. He runs our crypto business. Deepak Rao, who presented at the Gold event and runs Banking now and our credit card, he’s the general manager of money. He’s running his own PnL and business as well. Then we have a couple of GM’s in different areas that are building businesses. JB Mackenzie runs futures and also prediction markets. He’s got international brokerage responsibilities. There are a few others here and there, a few earlier stage efforts, but those are the big businesses. We also try to give full accountability, full responsibility, to our GMs so they have their own product resources. By and large, they have their own engineering resources as well. Although we have central platform engineering that builds the underlying technology for everything.

Design and branding is more so centralized under me because I think it’s important for all of our business lines to have a cohesive design language and also cohesive story when they communicate to the public. Those remain centralized, but most everything sits under the GMs.

That’s unusual for a startup of Robinhood’s age. Most startups at this time are still pretty functional. Everything rolls up to the CEO. Have you structured the divisions in this way because of regulatory concerns, or because it’s more efficient? The app is still the app. You express all of Robinhood to the user as one single app. Why have you broken out into divisions inside of that app?

We do have multiple apps. We’ve got a crypto wallet, which is a separate app, and banking is a separate app. Then there’s the main Robinhood app and all of our trading and investment services are in that one. So we do have three apps, but you’re right in that the GM divisions are not per app. GMs collaborate and share app services and I have a product leader that manages the core app. They’re in charge of navigation and design of the overall experience. We try to solve it that way.

But there’s puts and takes with every org structure. When people are separated in divisions, as you say, then it becomes a little bit harder to find ownership over the core surface areas because that’s not natural. And also, the tension points where they interact or where maybe they have different goals bubble up to me or to the core product team. We’ve tried to engineer around that by making those tension points at least knowable and specific. We know it’s going to be design, core app, and marketing.

But yeah, the flip side is if everything’s functional and you’re rolling out multiple businesses, then nobody owns the PNL (profit-and-loss) of those businesses. If I ask someone, for example, “Why is options market share the way it is or options revenue?” They’re like, “Well, I don’t know. I’ve got the product. The product’s great. The engineering is working according to spec.” But the PnL accountability for all business lines would be me. There’s not one person in that structure besides the person at the top that’s living and breathing and losing sleep over the business results of what they’re working on, which is, I think, a flaw. At least for us, which is a multi-product line, multiple entity business, I think it’s worked really, really well.

We made that transition in 2022, and I think since that point, the results have become apparent. I think all the GMs feel huge accountability and responsibility over their entire businesses. They have more ownership. They love it, and I think we’ve been executing really, really fast. It’s worked very, very well for us, but not without risks that have to be managed.

I think there is a nice thing about it being aligned with the regulatory structure. We’re regulated. We have lots of regulated businesses. Each of them have different licenses. A lot of the time, the regulations stipulate that the business needs to have a president with actual authority, a chief compliance officer, and so aligning the regulatory structure to how we operate very, very closely just reduces complexity.

I think in a functional structure, you have to fight against that and compensate for that to some degree. Other people have strong feelings about actually hiding the regulatory structure from users and absorbing that complexity as an organization. But I think if you can figure out how to align with it and actually use it effectively, it saves time and streamlines things so that we’ve embraced it rather than fought against it.

The structure question is the big Decoder question. The other one I always ask everybody is how do you make decisions? What’s your framework?

I would say I operate at opposite ends of the spectrum. On the one hand, I’m a math and physics person. I love data, I love numbers. I’m very quantitative. I like digging into the details and breaking things into constituent bits; I’m reductionist in that way.

One of the values that we have is first principles thinking. I’m generally allergic to thinking by analogy. “Oh, this is the way it worked at E-Trade,” for example. When I hear something like that, I immediately get skeptical. I don’t love reasoning by analogy. I don’t like doing things just because others have done them that way. We have this saying, “We only follow the crowd when they’re right.” I don’t want to be contrarian for the sake of being contrarian either. I think that’s silly. But the ultimate thing is “is it right?” And we’ll follow the crowd if they’re right. If they’re wrong, we’ll gladly go against them. That’s one side.

I think the other side is I’m also incredibly comfortable just doing things based on gut feel. I think you need that in order to actually push design forward, because design by its very nature is not super quantitative. A good design is opinionated, which means you’ll piss people off who disagree with it. I have no problem with that. I’d like to say the endpoints are important. It’s good to make some decisions intuitively based on gut feel, others quantitatively, and generally the middle takes care of itself.

Let’s put some of that into practice. You’re big on prediction markets. I know you have a lot of thoughts there. I’m eager to dig into them. This is the rare Decoder where there’s breaking news on this show that is nominally about org charts. Just before you came on to tape with us here on Friday, March 28th, the New Jersey Department of Gaming Enforcement, which calls itself Nudge (NJDGE), asked you to halt bets in New Jersey, on prediction markets on March Madness specifically.

I’m just going to read the quote: “This activity constitutes a violation in New Jersey sports wagering acts. Which only permits licensed entities to offer sports wagering to New Jersey residents on collegiate sports events occurring in New Jersey.” It’s similar in Nevada. The quote from the chairman of the Nevada Gaming Control Board: “Every sports pool in Nevada must undergo an extensive investigation prior to licensing.” Massachusetts is also investigating this.

You’ve halted trading in New Jersey, you’re complying with the cease and desist there. It’s a big decision to go launch in these markets when you know that there’s an enforcement authority, particularly in New Jersey and Nevada where they have casinos at scale. Why make that decision? Why not go to them first and say, “Are we in compliance?”

This is sort of new ground. If you think about the history of how this came about, Kalshi had a big lawsuit.

Kalshi’s your partner on prediction markets.

Yeah. For prediction markets we’re operating under the CFTC regime, which is the Commodity Futures Trading Commission. They regulate futures and swaps, and prediction markets falls under that purview. We registered to be a futures commission’s merchant, which is basically the equivalent of a broker, but in CFTC land. And companies like Kalshi, which we partner with for these particular contracts, also ForecasteX, which we partnered with for the presidential election prediction market last year, they’re called designated contract markets (DCMs). They’re like the exchange to our broker.

With all prediction markets, since we’re not a designated contract market, we rely on the DCMs to list contracts. And once it’s listed by a DCM, which again is the exchange in CFTC land, we can list them on our platform. Our view is we want to list all prediction markets. We believe that they have societal value in addition to any value they have as a trading asset for our traders. We think they’re a better source of information.

Obviously the line between prediction markets and what should be federally CFTC regulated and what should be under the purview of states who have gaming — which is regulated and taxed at a state level — that line is going to be debated right now. I think Robinhood’s a big part of that because we believe in prediction markets. That’s the intersection here, particularly with sports. While we believe that these are CFTC regulated products, we also recognize that this issue has to be debated and worked out, and it’s not very, very clear.

For that reason, we decided to respect the state of New Jersey’s demand to halt operations for its citizens, even though we disagree with it. We’re going to work it out over the next couple of months. We’ll be in conversations. But as you can imagine, there’s a lot of states — there’s a lot of people, a lot of counter parties — that could take issue with various aspects of it. And a lot of established interests are at play here. I think this is going to be an interesting area to watch. But I do believe prediction markets are the future, and they have societal value across all categories.

Were you ready for this? When you launched it, did you know a bunch of states are going to get mad and we might have to geolocate our services or halt them in certain states?

Well, we launched without Nevada, as you know. Yeah, of course we built the capabilities of that, as we have in the traditional non-prediction markets business. Crypto also has a state by state component to it. For example, in New York, we don’t offer crypto transfers. You can’t transfer in and out. There’s differences between the coins that are available on a state level. Up until recently, we weren’t in all 50 states. It’s nothing new to us. There’s a state component to everything that we do.

But were you expecting New Jersey to show up and say, “Turn this off until we deal with it”?

I don’t know if we were expecting New Jersey in particular, but obviously it’s not a surprise that if we’re in this new area where states have vested interests to make sure that it’s state regulated that they would have concerns.

The argument that you’re getting at is the difference between a prediction market and gambling. But straightforwardly, that is what is happening here. The states are saying, “We regulate gambling in our states. You pay taxes, we have revenue. We want to protect our citizens. This looks an awful lot like gambling. Go ahead and stop.”

I would offer you the opposite argument. I know a lot of people who believe the markets are gambling, that merely investing in the stock market, or meme coins and meme stocks, is a kind of gambling that has taken place because it has been democratized by apps like Robinhood and even E-Trade before it.

I see the difference there very clearly. In the stock market, you should be able to look at the fundamentals of some company or its earning reports and you should be able to derive some secondary value. “I understand what this company is doing, I understand how much money it’s making, how much money it’s losing, where it’s investing, what its opportunity is. I can draw some line to its future stock capability.”

That is the most important thing that undergirds the market. That’s the argument against “the market is gambling.” There’s some mathematical reality there. What is that same argument for a prediction market on sports? Because you can’t go look at the Lakers and say, “Well, LeBron’s there, so they’re definitely going to win every game.” That’s just not how it works.

You’re making a valid point. I think the line between gaming and gambling and finance is a debated thing. There’s people that will go on Twitter and say, “Anytime you’re taking a risk, it’s a form of gambling.” I think the term is not properly defined and specifically defined, which I think adds to the confusion. And in particular when you deal with derivatives markets, which I think prediction markets are a subset of the overall derivatives market space, there’s several types of market participants. There’s folks that are coming into a market to hedge, and if you’re a farmer, then you’re sensitive to crop yields and rain and weather and all sorts of things.

One of the original use cases was for these derivatives markets to apply to farmers for them to hedge their exposure so they can smooth out their returns and their risk over time. And actually, I think for these types of historical reasons, the CFTC and these derivatives markets are overseen by the Senate Agriculture Committee [specifically the U.S. Senate Agriculture Subcommittee on Commodities, Derivatives, Risk Management, and Trade], which is a weird historical fact. And now crypto being in there has a side effect of Senate Agriculture overseeing crypto. But yeah, it’s the historical reason of futures and derivatives being especially valuable to farmers.

You have hedging, which is one use case, but you also have speculation. Speculation is people just making predictions on what the price is going to be in the future. Without the speculators, it’s not an effective market for hedgers because you can’t just have people taking the opposite view of what’s going on in reality because then it won’t be an effective hedge, so you need the speculators to be in there speculating in order for the market to be liquid.

Then you also have arbitrageurs. And arbitrageurs, which is how I began my career as a trader, just look at all markets and, using technology, compress the prices. If you have the same thing trading in two different places, you just buy it where it’s cheaper, sell it where it’s most expensive, and eventually the prices converge. These are the three types of participants necessary to make any derivatives market work. And so now your question is if you look at folks that are speculating, is there a difference between speculation and gambling?

Let me make that question more specific just based on your example. My father-in-law is a farmer. I married a farmer’s daughter. The utility of him being able to hedge is very clear. Yes, it’s historical and, yes, now the regulatory scheme has this quirk of the [Senate Agriculture Committees] overseeing the derivatives market, but we all still got to eat, right?

Yep.

The farmers have to stay in business. The utility of that remains exactly the same as it was when these regulations were initially passed. And then you need to do some market making. You need to have the speculators and the people doing arbitrage in order to create the market for the hedging. But the utility of that for the farmer and then downstream of the farmer, us literally filling our plates, is obvious. What is the utility of that for sports? For the Lakers. Are you trying to hedge against the risk of losing for the Los Angeles Lakers?

I’ll tell you that sports is a big industry in the US. There’s lots and lots of different types of businesses that rely on sports and the sports industry economically. And it’s gotten much bigger. It’s not just like fans, but sports betting, since that’s been legalized, has just grown to tens of billions of dollars. And it’s still much smaller than what it would be in Europe.

Do you think that’s good? Do you think sports betting is good?

Do I think it’s good? My view is people should be allowed to do what they want with their money. Yeah, I think that markets are good, generally individual accountability is important. There’s folks that trade very, very actively and process lots of information and actually are quite scientific about taking advantage of mispricings. And as a former arbitrageur, I do think that that has value. I want to get away from actually trying to judge every contract on an individual level because I think you can get into trouble. Of course, maybe I can come and give you examples of contracts that I don’t think are great and I wouldn’t trade personally, but I think prediction markets does have significant societal value.

It’s an evolution of what the newspaper served in the past. You have the front page, which is events that people want information about that are trending right now, then you have the business section, arts and leisure, style, and of course you have sports. And the newspaper obviously had value. People were paying for it after the fact. Prediction markets actually give you that news faster; in some cases before it even happens. I think it certainly has enormous economic value.

I view sports as a subset. It’s one of the categories of information and news that people really, really care about. That’s why it’s so interesting to people and people are going to want to protect their purview over that domain. But yeah, I would distinguish prediction markets from gambling in that way. I have mixed feelings obviously about gambling in general, but prediction markets I’m a big believer in.

When I said I had 900 pages of questions, by the way, that thing you said about information, that’s 850 of those pages. We’re going to get into that. But I just want to stay on this for one more second. What specifically to the user, as expressed in your app, is different from betting on sports versus buying a contract in a prediction market? Because I looked at Robinhood today, and I understand there’s some difference and there’s some vocabulary differences, but what I saw was I’m looking at March Madness, and if I pay 80 cents for a contract and this team wins, I’ll get $1. And that feels a lot like betting. It was Auburn, by the way. I don’t know if they won or not.

Yeah, they’re the No. 1 seed. Traditional sports betting, let’s say digital sports betting, not even on-premise stuff, there’s a house. That means that when you enter a bet, you’re basically betting against the house, and with that comes all of the negative effects. There’s no market, the house is just giving odds. There’s a line. They’re setting the line, and if you win too much, you get kicked off the platform, which is unfortunate. In most cases, once you’re locked in, you can’t get out of your bet.

Because this is a market, there’s no house. Buyers and sellers are meeting directly in an exchange. We’re crossing orders, which facilitates price discovery. Since there’s no one setting the line, the market sets the line. It becomes a more effective prediction, and from the user standpoint, the spread gets tighter because, for a variety of reasons, price discovery leads to tightening of spreads. I think that’s the major thing. There’s no house. Buyers and sellers meet. You can get out of a position during a game, which at [sports] betting platforms is not a commonly offered feature. It’s very similar. You get all the benefits and the power and the rigor of financial markets.

But just at the base level, some 20-year-old kid downloads this app and they want to wager on March Madness, the technical implementation of “put in some money and get some money out if the team you’ve predicted to win, wins” is different. And I think the regulatory approach you’re taking is different. You’re saying these are effectively derivatives contracts and you should be regulated differently because it’s not traditional gambling. But the effect on the user is the same.

The reason we regulate gambling is because it has bad collective effects in society. People can get addicted to it; they throw their savings away. There’s a lot of reasons outside of the technical implementation of “the house sets a line and can move against you.” There’s reasons that we regulate it. Do you think those reasons are applicable to what you’re doing with derivatives contracts? Because I look at it from the user pushing a button, and the button says, “If they win, you get money,” and the technical implementation of that doesn’t really matter.

I think some of those reasons are applicable. A lot of the origins of the state-by-state regulations come from a world where you actually had physical places where you would go. And so these turning into digital platforms in and of itself, not even CFTC but also state-regulated gambling, are new things. I think the regulations have to evolve either way. But yeah, certainly we want to make sure that suitability and all of those checks are followed through.

And I think actually the traditional financial markets, futures markets are highly regulated. You do KYC (Know Your Customer regulations), you do monitoring and surveillance. There are suitability checks that make sure people really know what they’re getting into and they have to self-certify. And I think that’s a benefit for prediction markets being in the CFTC regime because you have high standards. Saying that these are financial markets isn’t, in my opinion, a lowering of standards in any way, I think it’s a heightening of standards.

Well, the standards don’t exist yet, as applied to this specific thing. The standards exist abstractly for derivatives markets, and now we have to apply them to this behavior. And at least some states are saying, “Actually, this just looks like gambling to us.”

Yeah, but what I’m saying is CFTC-regulated markets are highly regulated. It’s not accurate to say that there are no standards, because we’re following the CFTC standards, which are very rigorous.

One of the things I worry about with our audience, we have a lot of young men who listen to the show, and who read The Verge**, is a sense that these types of markets — whether it’s crypto, the regular stock market, derivatives, prediction markets, or just FanDuel — are a quicker path to riches than regular work. There’s a sense that we’re replacing the American dream with a very financialized secondary market economy. Is that how you want people to perceive Robinhood, that this is the future of the American dream?**

Yeah, I did write an article, back in I think it was 2021, about how the American dream itself as a concept has evolved. It used to be very tied to homeownership. You’d buy a house, you’d get a 30-year fixed mortgage, and that was the American dream, and that’s actually not ideal from an investment standpoint. The amount of interest in fees you’re paying on that, if you view it from an investment standpoint, is actually incredibly high. If you’re going into U.S. equities — which are now commission-free and very, very low cost — that the American dream should perhaps evolve towards U.S. equities.

I didn’t make the claim that it should be crypto and derivatives or all of these things. And in fact, a couple of days ago, we actually crossed the bridge from being a purely self-directed platform into offering investment advice with Robinhood Strategies. If you look at the asset allocations of the portfolios there, it’s very much listed equities and ETFs. And then if you actually look at what we incentivize as business, what we’re giving matches for, it’s things like retirement where you get a 3% match on contributions.

I think I would distinguish between what the right way to invest is for the bulk of your money, which I do think for most people that have income and assets should be passively managed. But also, I do think people that have the income and can passively manage a portion of it, I don’t think it should all be passively managed, I think there is a room in your portfolio for every person for it to be actively managed. That could be in things that you have high conviction in, whether it’s individual stocks, cryptocurrencies, or options. If you’re at a startup, you implicitly have high conviction and lots of concentration in the company that you’re actually working for. And if you consider yourself an expert in an industry or even in sports, I think the derivatives markets live in that bucket.

But yeah, I wouldn’t say if you look at Robinhood, the actual mission and the future vision is for us to manage every dollar. I don’t think every dollar should be in derivatives markets; probably a small portion of them. But the reality is people bet on sports, people engage in derivatives trading, and that’s money that’s leaving Robinhood accounts. If we can serve all of those dollars with our platform in a seamless and easy way at the lowest possible cost and the best user experience, then we’ll have full wallet share with our customers across multiple generations. I think we could both add value and build a significant and important company that way.

“Wallet share of our customers across generations,” is an all-time Decoder phrase. I thank you for it. It’s going on the wall. Let me ask about information and risk. What you’re describing is a spectrum of risk. You’ve got your new bank accounts, you’re paying people, what, a 4.5% yield — that’s low risk. That’s just your bank. All the way on the other hand, you’ve got prediction markets for sports, which are maybe the most risky thing you can do. And then in the middle, you’ve got your thesis about information. Prediction markets are this new source of information.

The thing that gets me is when you make prediction markets, the value of the information skyrockets, and then you have a lot of incentive. You’ve created an enormous incentive to affect the outcome. In the best case, you work at a startup, you’ve got stock in the startup. You have a huge incentive to affect the outcome positively. The company will be a success. You’re going to work really hard. You’re going to make a lot of money.

I look at the NFL, for example. I’m a big NFL fan. The amount of time we now spend talking about referees in the NFL officiating because of gambling has gone up. The notion that the league is scripted and that the games are rigged because any individual referee can make one penalty call at the end of the game and shift the outcome is skyrocketed because of the inclusion of gambling by the NFL into the product itself. That feels like a bad outcome to create all of these incentives to shift the outcome without any regard for the quality of the outcome itself.

How do you manage the prediction markets against that incentive? Because I see that as totally distorting and in most cases negative.

Yeah, I think that’s a great question. And that’s one of the areas where the traditional financial system already has lots and lots of infrastructure because we’ve faced this problem for decades. You have insider trading rules and regulations, and it’s very analogous to a company insider using proprietary information for their own benefit to make money in financial markets. That very much exists.

There’s also general anti-fraud protections that go into place when you’re not dealing with securities. If you remember, Coinbase had a case a couple of years ago with the DOJ and what they found was that some employees used knowledge of forthcoming listings. I think it was some meme coins, they bought those meme coins because they knew that they were going to be listed and made a bunch of money. And of course, this was caught and tracked by surveillance and they got in a lot of trouble. I think generally the same principles apply.

Sure, but how does that track with your sense that this is the new source of information? Because the information only enters the market if people have it and they begin trading on it. If you want to outlaw insider information, you have to prevent people who have that information from trading on it. How does that get into the prediction market?

Yeah, basically individuals who have proprietary information shouldn’t participate in the prediction markets, and all of the DCMs basically have rules against this. Because we know who’s making the trades, everyone has to be KYC’d (know your customer) at regulated DCM / FCM (futures commission merchant)-regulated prediction markets, we have the capabilities of identifying abuse. And of course all of these rules can evolve over time. If there’s new vectors for abuse as the markets expand, there’s mechanisms for those to be incorporated and to become new rulemaking.

Hopefully the rules should evolve, as with any system. And if there’s new vectors coming in, then we can evolve the rules to account for those. But I’m actually not sure if there are new vectors that aren’t accounted for by the existing rules. And I think this is one of those things where because the state regulatory regimes haven’t really accounted for this, they may be less well positioned to oversee abuse than the federal level.

Where does the information come from then? If I’m looking at a prediction market on Robinhood and the line moves sharply, that’s the information you’re talking about. This is the new source of information. You’re going to get it before the news gets it, or the traditional media gets it. You’re going to watch that line move and you know something happened before everyone else knows it happened. How do you get from that second order effect — the line moved, people started moving their money against some new information — to the information itself?

In the same way it happens in financial markets. You have sophisticated participants. Some of them are retail, many are institutional that actually make sense of all of the data that’s coming in real time and actually crunch the numbers and see what it means. And a lot of this is happening using automated computing methods. They’re crunching all of the data.

But yeah, you can think of it as, let’s say you’re watching the news on election night and you’re getting all of this polling data and all the early returns from the polls, and they’re telling you Ohio results just came in, and there’s this many voters in Ohio out of this many that are reported. There’s a process by which you take that and actually price what the likely outcome of the election is. And so the people that are really good and fast at doing that have an opportunity for profit.

That opportunity for profit isn’t the information itself, though. That’s what I’m getting at. I’ve heard you say the information line before. You said it to my friends, Casey Newton and Kevin Roose, on the podcast Hard Fork. You said you’re going to get information before it happens. That prediction markets are not just the future of trading, but also information. What prediction markets are “is the news faster.”

But here, you’re saying prediction markets are reacting to the news, they’re reacting to information. If you’re a regular Robinhood investor and you’re looking at the line move, how do you get back to, “Okay, the smart money made some decisions. The smart money is watching Harry Enten say on CNN, ‘Here are where the votes are,’ and now I’m repricing the contract? That’s not the news, that’s a derivative of the news.

[Content truncated due to length…]

From The Verge via this RSS feed