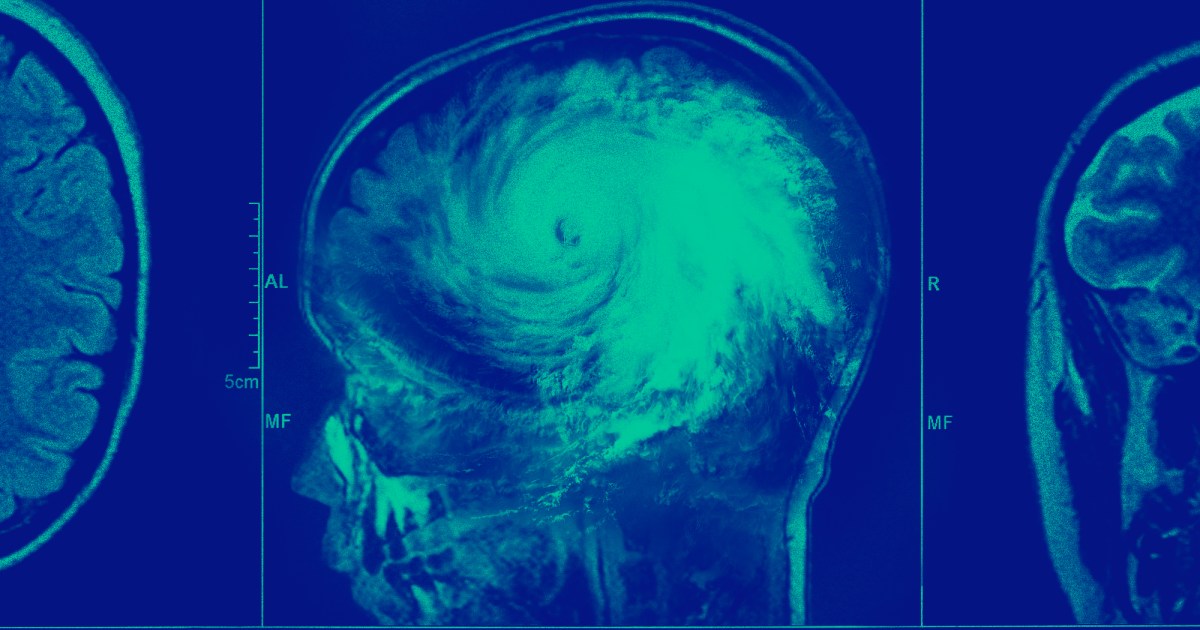

On March 10, around 9:20 pm, Marianthi-Anna Kioumourtzoglou, an environmental health professor at Columbia University, got the email she’d been dreading: The Trump administration cut funding for a new center she had been tasked with co-leadingcalled “Climate and Health: Action and Research for Transformational Change.” CHART focused on researching the effects of climate change on cognitive function, including how it might impact Alzheimer’s disease, a relatively understudied area. Within a week, her three-year, $4.2 million grant from the National Institute of Health (NIH) was terminated.

“It wasn’t exactly a surprise,” Kioumourtzoglou says. As Mother Jones first reported in February, the Department of Health and Human Services planned to shutter NIH’s Climate Change and Health Initiative, the program which funded Kioumourtzoglou’s center. Then, on March 7, a few days before the email, the Trump administration announced it would cut $400 million in grants and contracts for Columbia in response to its alleged failure to crack down on antisemitism on campus. Critics saw the move as political manipulation and an attack on academic freedom. (On Wednesday, Science reported that the government plans to put all of Columbia’s NIH grants on hold.)

Had CHART kept its funding, Kioumourtzoglou and her colleagues planned to conduct a nationwide analysis of more than 70 million Medicare records to study climate events and Alzheimer’s disease. They also planned a small-scale study of a few thousand people in New York City to examine the impact of these events on our brains at a molecular level. Kioumourtzoglou also hoped to bring on urban planners, computer scientists, engineers, sociologists, and others not traditionally part of climate or health research, for an all-hands-on-deck approach. “I think this could have revolutionized how we think about climate and health research,” Kioumourtzoglou says.

The risk the cuts pose to science, of course, extends beyond just one program. CHART alone is one of about 20 similar university-based centers around the country tasked with better understanding the impact of climate change—heat waves, cyclones, wildfires, floods, and more—on health. “If the others are cut as well,” Kioumourtzoglou says, “then the catastrophe is immense.”

Last week, I talked to Kioumourtzoglou about what the loss of CHART means for her colleagues, for understudied questions about climate and health, and ultimately, for all of our well-being.

This interview has been lightly edited and condensed for clarity.

Why did you want to study the link between climate change and cognitive function? Where did the idea come from?

These [climate] events, especially the very big ones, stress us out, simply put. Stress is associated with oxidative stress in the body, and that, in turn, with neurodegeneration. There’s a study linking wildfire smoke and dementia. So there has been some limited evidence that there might be something there, but we don’t exactly understand those pathways.

What happens when we’re exposed to multiple of these threats simultaneously? Wildfires commonly occur with heat waves and drought. What happens if we put all of these things together? And what’s the response[to these events] in the body?

When you got the email saying that your funding would be cut, what did you think? Were you expecting it?

It wasn’t exactly a surprise. That said, I don’t think anyone believed or expected that they would do this. I think the idea was, Okay, even if they cut it, they would at least let us finish the year. The contract is for the year.

The School of Public Health is what is called a “soft money” institute. That means faculty need to raise about 75 percent of our salaries. So there are 20 co-investigators on this grant, with various levels of percent effort covered. That means it has a direct impact on our salaries. That is probably the least of the problems.

Climate change, whether some people choose to ignore it or not, is making these extreme weather events much more intense and much more frequent. We saw it even this year with [Hurricane] Helene and the Los Angeles wildfires. These events are here. They are recurring. They are extreme, and are becoming more extreme. And they impact every aspect of life.

At the same time, Americans are aging. So, understanding the impacts of climate change on our aging population is very important. First, we need to understand it, and then we need to start working on strategies for prevention, mitigation, adaptation—anything we can do to potentially extend our health span.

Do you have any idea how the 20 co-investigators on this grant are going to make their salaries up? Are there other grants they can apply for at this point?

Yes and no. This was not the only grant that got cut. So there are people who have lost, across multiple grants, up to 30, 50, 70 percent of their salaries. So far, we’ve had two paychecks. I’ve at least received a full paycheck. But I don’t know how long this can keep going.

In theory, we can keep applying for grants. That’s the idea, right? That’s the job. But with the general impact on climate and health research, if that’s your expertise, then sure, you can keep applying. But NIH, clearly, is not going to fund this work for the foreseeable future. There are foundation grants that we can apply for. But now, competition for those has skyrocketed. So it does not look great.

One concern I’ve heard from researchers is that, in applying for grants, using a term like “climate change” will mean proposals will not be funded. So, the hope was to write around it, using words like “extreme heat.” Is that something that can even be done with your field of research?

One potential solution would be to rephrase certain terms. [But] ultimately, this will impact how we protect the most vulnerable populations, if I cannot even say “vulnerable population,” if I cannot say “race,” I cannot say “women,” in my grants anymore.

“Say you’re an oncologist, and a patient comes in with liver cancer, and you cannot say the words ‘liver’ or ‘cancer.'”

It would be similar to, say you’re an oncologist, and a patient comes in with liver cancer, and you cannot say the words “liver” or “cancer.”

A theme I’ve been hearing in my reporting is that the Trump administration’s cuts will disproportionately impact early-career, younger researchers and postdocs. Is that the case here?

Our postdocs are, thankfully, unionized, so they are okay until June 30. We had three master’s students working as part-time research assistants on this grant that I had to lay off. There’s no money to cover them. Tuition is expensive, and this was their income source.

I interviewed someone who’s finishing her PhD now in a different institution. She was an amazing researcher. I was going to hire her under this grant, and now I cannot. Many people with grant cancellations across universities cannot hire new postdocs.

The impact of this on the future of research is going to be—it’s unquantifiable at this point, right? Many institutions will not admit PhD students this year. Our students at Columbia are unionized, so they have guaranteed funding. But even before unionization, our department guaranteed funding for five years. If we cannot guarantee funding, we cannot have incoming students. If we don’t have incoming students, we are not training researchers to do public health research. The long-term implications of these cancellations are huge.

We covered lots of ground. Is there anything else you’d want people to know?

We are all at a loss here for understanding why these cuts are happening. [Columbia’s] Alzheimer’s research center was terminated. Cancer centers were terminated. Our training grants were terminated. This will impact all of our health.

“This will impact all of our health.”

And it doesn’t sound—Yeah, sure, some very fancy elitist school lost some money. They have billions in an endowment. It’s not a big deal. But it is a much, much larger deal than we all understand. And maybe the government is flexing, and funds will be reinstated, and things will go back to normal. Maybe. But if that doesn’t happen, and it might not happen, unless people start calling their representatives and their senators, because this will affect their health and the health of their loved ones.

We’re not doing this for our salaries. We are all in this because we want to help understand and prevent disease. So it’s truly devastating.

From Mother Jones via this RSS feed